Sandra Hsu Hnin Mon woke on 1 February extremely angry and anxious. For the infectious disease epidemiologist and Center for Human Rights and Public Health (CHRPH) senior research program coordinator, news of the coup was simply unacceptable. She, along with thousands of co-nationals, immediately kicked into action as part of Myanmar’s Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM).

Ever since, Sandra Hsu Hnin Mon, has been helping to organise the diaspora community and CHRPH with data collection and documenting the post-coup crackdowns from a health care perspective. She acts as powerful node in Myanmar’s globalised network of health care actors communicating with those on the front lines while pursuing advocacy with US government.

She is outraged and determined. There is ‘escalating violence against health care workers and the health care system is happening in the middle of a still raging pandemic,’ she decries.

Myanmar’s decades of civil war and military dictatorship has rendered almost every aspect of its public health concerns amongst the weakest of any country world-wide. In the context of the post-coup crackdown and Covid 19 pandemic, said Jennifer Lee, CHRPH’s Myanmar campaign co-ordinator, Myanmar has reached yet another low point.

Sandra Hsu Hnin Mon and Lee spoke on Monday in a webinar titled Protecting the Right to Health in Myanmar/Burma's Spring Revolution to launch a report documenting and analysing early data on the health-related human rights violations including the deliberate obstruction of health care by the Tatmadaw troops during the coup.

The report, Violence Against Health Care in Myanmar 11 February and 12 April 2021, is jointly released by the CHRPH at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Insecurity Insight and Physicians without Borders. According to Lee, the organisations are collaborating on documenting forensic evidence of crimes of excessive use of force against protestors and against detainees.

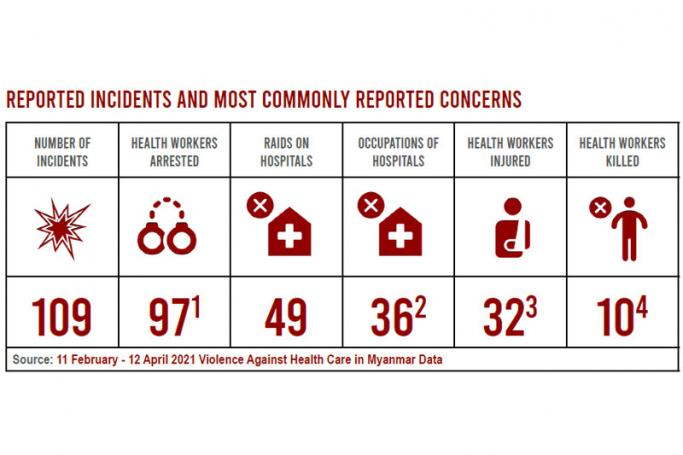

Initial key findings are based on data collected between 11 February and 12 April 2021 are as alarming as accumulating new reports indicate. 109 incidents of violence against health care have been forensically documented throughout the country, many in Mandalay, Yangon but also in Ayeyarwady, Chin, Kayah, Mon, Sagaing, Shan and Tanintharyi states and Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory. Significantly, Tatmadaw soldiers or associated police forces were the reported perpetrators in all incidents.

However, this is far from exhaustive as much data is still missing because the military is actively cutting communications. Further, notes Mon, data is being missed from rural areas where attacks are potentially more severe because they are poorer areas lacking adequate internet coverage.

Health Care Workers as Targets

Myanmar’s health care workers were applauded for their bravery as they take part in what Professor Chris Beyrer, CHRPH Director, described as ‘a life-or-death struggle to protect, defend and restore democracy to the country’.

Health care professionals are credited with beginning and sustaining their participation in the CDM movement by refusing to work in military hospitals. They are also frontline responders to victims of security force violence with many facilities stretched beyond limits responding to emergencies.

The report has documented at least thirty-two health care workers injured and ten killed in the violence. Emergency medical teams have been shot at while trying to retrieve or treat injured civilians at protests. In some cases, health care workers were killed in close-range shootings.

Ninety-seven health care workers have been arrested and as of last week 120 arrest warrants have been issued for health care professionals all around the country. This number is expected to rise next week.

Health care workers have been arrested without warrants at their places of work and at home during the day and at night. This has caused many to flee into hiding which further diminishes their ability provide critically needed health care, Lee elaborated.

Health workers have been personally intimidated, arrested and evicted from government housing on suspicion of participating in the CDM.

Systematic Denial of Health Care: Hospitals and Health Care Facilities

The report also documents how the junta is actively blocking access to care for people injured, wounded and shot by their troops while participating in the CDM. Private clinics and hospitals across the country were issued with official directives mandating that injured civilians could not be seen or treated without first notifying the military.

Forty-nine hospitals have been raided and thirty-six occupied by security forces. On the night of 7 March over 20 hospitals were occupied throughout the country. Myanmar military forces used live rounds, stun grenades and rubber bullets during these forced entries. In some cases, CCTV records were erased and medical supplies destroyed.

Raids have been documented on aid offices and organisations’ storerooms containing medical equipment following organisations’ provision of medical care to protesters. Further, verified reports tell of teargas being fired inside hospitals while health workers were trapped inside, staff were beaten and patients’ rooms searched.

Today, almost every private hospital has Tatmadaw troops stationed out front servicing to intimidate people from coming to the hospital, particularly those affiliated with the CDM.

As well as cases of harm being directly inflicted, medical professionals report harm caused by their denial of access to people who have been detained. This is the case for individuals with pressing medical needs pre-existing and inflicted upon them during torture by military while under arrest, explained Sandra Hsu Hnin Mon.

Conditions have recently worsened as night curfews are now being enforced with the military regime’s reimposition of the Township Household Registration Law which is preventing people from seeking health treatment in safe houses or seeking assistance at clinics overnight.

Emergency transport vehicles are being targeted by the security forces with documented incidences of ambulances being shot at, confiscated and damaged.

Summing the health care in relation to the crackdown Lee said, ‘you are at risk trying to provide medical care, you are at risk trying to seek medical care, you are at risk during the process of being transported to find medical care. This is a very grave situation.’

Covid Response Decimated

The graveness of the health situation deepens steeply in the context of the Covid 19 pandemic. Prior to the coup, noted Beyrer, Myanmar was leading the way relative to regional neighbours in terms of getting the vaccine to health care workers. Indeed, anyone in the entire health care work force who wanted to get the vaccine had their received their first doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine manufactured by the Serum Institution in India (SII).

However, Myanmar’s Covid 19 response was also violently interrupted by the coup. The State Administration Council (SAC) privatised the national vaccine roll-out program and, consequently, vaccinations efforts have been severely dampened by widespread civilian distrust of who is administering the vaccine and the systematic desecration of Myanmar’s health force. Those who received their initial doses have not received their second.

Covid 19 testing has also collapsed. The SAC’s Ministry of Health and Sports has reported a daily average of 33 cases day since Feb 1 compared to a daily average of 357 cases and 10 deaths up until 31 January. ‘The numbers are clear,’ said Sandra Hsu Hnin Mon, ‘we are seeing the surveillance capacity for Covid stripped to its bare bones.’

Now, just as third and fourth wave variants are appearing and spreading globally, Myanmar’s internal displacement has reached a 20-year high and many are precariously teetering on border-crossings into neighbouring countries. Thus, Myanmar’s alarming Covid situation poses not only a regional issue but a global security issue. Beyrer warns that this threatening insecurity scenario needs to be kept in clearly in mind.

All pre-existing health services and programs beyond the Covid 19 pandemic, such as HIV/AIDs, TB, Malaria and family planning, have been disrupted. Regarding Myanmar’s whole heath care system, observed Beyrer, Myanmar ‘is moving into a data free zone.’

Documenting Myanmar’s Dual Health-Related Human Rights Crisis

Lee explained how she and her colleagues are looking to document the full scope of crimes against health that have been occurring since the coup. A lot of documentation that is occurring is informal, such as photos taken at a distance and shared on social media. While this is important, there is also a need to ensure documentation meets evidentiary standards to be used as evidence in justice and accountability mechanisms in the future.

Lee had previously worked with CHRPH to forensically document human rights violations against Rohingya amounting to atrocity crimes. This work was shared with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and relevant actors and other accountability mechanisms trying the Myanmar Government on charges of genocide.

Researchers are working with colleagues on the ground to collate medical documentation such as photos, x-rays and medical records of injuries and crimes. They then partner with forensic experts to provide forensic evaluations of the impacts revealed by the evidence directly on people’s health.

Additionally, Lee and her colleagues are helping training medics and physicians on the front line to increase their ability to collect forensic documentation. This includes identifying the elements that meet those standards such as providing context and making sure photos show the injuries and reference measures.

‘It takes courage to report these attacks on health care workers and protestors,’ noted Len Rubenstein, epidemiologist and Director of Conflict and Health Program at the CPHHR.

Health and Human Rights

The military has stepped beyond its bounds to indiscriminately target health care workers and health facilities in ways that very much violate medical neutrality and their responsibility to ensure access to health care for the citizens of Myanmar, said Lee.

Recalling the military junta’s historical campaigns of oppression and genocide against the Rohingya, Rubenstein explained how attacks on health care have long been central to the Tatmadaw’s wars against its own people. ‘Whether you needed or provided health care, you were targeted because the junta’s strategy at its base was to diminish the whole population.’

Rubenstein went onto debunk a myth that by participating in the CDM, health care workers become political actors and removed from protection under human rights and international humanitarian law. ‘That is profoundly wrong. Lack of political engagement and neutrality is not a prerequisite for immunity from arrest, from punishment or any other kind of sanction. And the same goes for institutions like hospitals. They enjoy protection for free expression and also offering health care services to others.’

May 3 marks the fifth anniversary of the United Nations Security Council’s landmark Resolution 2286 Strongly Condemning Attacks against Medical Facilities, Personnel in Conflict Situations. The resolution requires governments not only to respect it themselves but to ensure that perpetrators face consequences for violations and that other governments act to ensure that the violence stops. ‘We have seen in Syria and Yemen that governments have ignored this resolution,’ concluded Rubenstein, ‘we can’t continue here.’