Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is up against a huge challenge in what Beijing had started considering as its backyard.

Myanmar pro-democracy protestors, who see China as the main backer of the military junta that seized power on February 1, have started attacking Chinese business interests as never before.

The anti-Chinese violence is reminiscent of the one that swept across Myanmar in 1967-68 when the Ne Win led military regime, resenting Chinese backing for a Communist insurrection, provoked public anger against Chinese business interests. Twenty years later, China regained trust of the Myanmar military Tatmadaw by backing its ruthless suppression of the 1988 uprising and ended up turning Myanmar into a satellite. Or so it might have thought.

The first jolt to its ambitions came into 2008-09 when Kachin people successfully opposed the $6 billion Myitsone dam hydropower project, triggering a furious reaction by Burmese civil society and democratic parties. Aided by the global human rights and anti-big dam environmentalist groups, the Burmese people finally forced the quasi-military regime of General Thein Sein to stop the China-funded project in 2011. A decade later, despite intense lobbying, Beijing is not anywhere near resumption of the mega project.

But now Beijing, seen as the main backer of the Myanmar military junta, is having to bargain for something much worse.

Pro-democracy protestors, mowed down by military gunfire on the streets of Myanmar’s towns, have turned to Chinese-financed factories and businesses, setting them on fire and even attacking managers and workers, personnel caught in the cross-fire of the conflict.

The protestors who want the restoration of parliamentary democracy in the country and a scaling down of the military’s influence, appear to believe that attacking Chinese business interests will force Beijing to pressurize the Burmese military to back down, hand back power to the elected lawmakers and allow Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi to form a government as was due to happen.

The Chinese were upset with the Suu Kyi government because it not only refused to resume the Myitsone Dam project but also cut down the investment size of the Kyaukphyu deep sea port project and drafted in other foreign partners for the Yangon City Mega project in July last year, refusing to hand over monopoly of executing the project to the China Communications Construction Company. This Chinese firm was accused of corruption in as many as 10 Asian and African countries where it is undertaking infrastructure development projects.

So far over 30 Chinese-funded factories have been burnt down. Chinese businessmen are complaining of huge difficulties in doing business from sourcing jade in the Mandalay wholesale market to running the Letpadaung copper mining project. Interestingly the Chinese joint ventures are mostly with Burmese military backed companies – so hitting one impacts the other. Protestors are also threatening to blow up the Kyaukphyu-Yunnan oil-gas pipeline linking a China-financed deep-sea port on Myanmar’s Rakhine coast to its Yunnan province. If the military repression does not stop and the largely peaceful protestors

turn more violent leading to the emergence of armed urban insurgency in the Burmese heartland, terror attacks on key China-funded infrastructure is a distinct possibility. That would seriously threaten the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), one of the two key BRI growth corridors along with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

The CPEC in Pakistan is also under attack with a surge of deadly attacks by Baloch separatists who resent the exploitation of their mineral and hydrocarbon resources by Chinese companies who have encouraged the Imran Khan government into granting huge concessions. Security risks and costs of the US$60 billion CPEC project are rising amid a resurgence of the deadly attacks by separatists in the troubled Balochistan province but the CPEC projects are also upsetting the Shias of Gilgit and Baltistan where the CPEC starts.

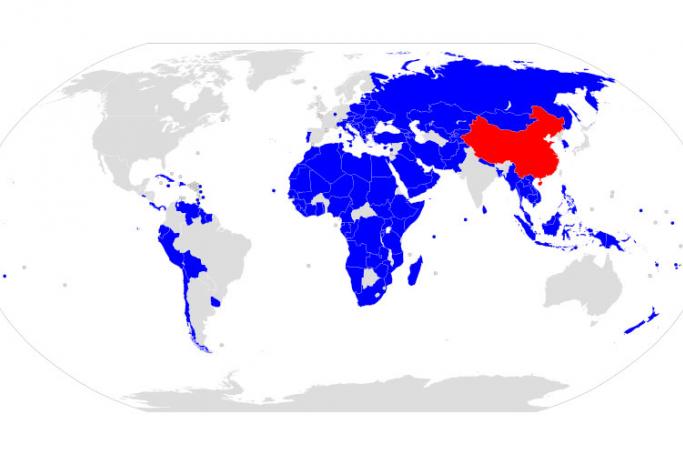

Scores of China-funded huge infrastructure projects have been cancelled or are on hold in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Philippines. Bangladesh torpedoed the Chinese deep sea port project at Somadia and handed over a similar project to Japan on its southern coast. In Sri Lanka, the long leasing of the Hambantota port to China after the government realized its inability to service the unsustainable debt, has created not only such angst against Beijing and its friends in the island nation but send out a global alarm on Chinese-funded project, raising serious doubts about Beijing’s motives in driving up the project scale and then bargaining for outright long-term control over national assets – the ‘debt burden strategy for economic and political control’, as some Western geo-strategists have described it.

But in keeping with the Newton’s law of every action generating an equal and opposite reaction, China, rapped for not handling the COVID-19 virus in a more timely manner, is being viewed at the world’s leading ‘neo-colonial’ power, hungry for resources and determined to extract them, unmindful of the adverse impact on countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and Europe.

The Dragon has grown in power but its new “Silk Road” outreach is growing increasingly unpopular with governments and the local people directly affected by the infrastructure and projects.