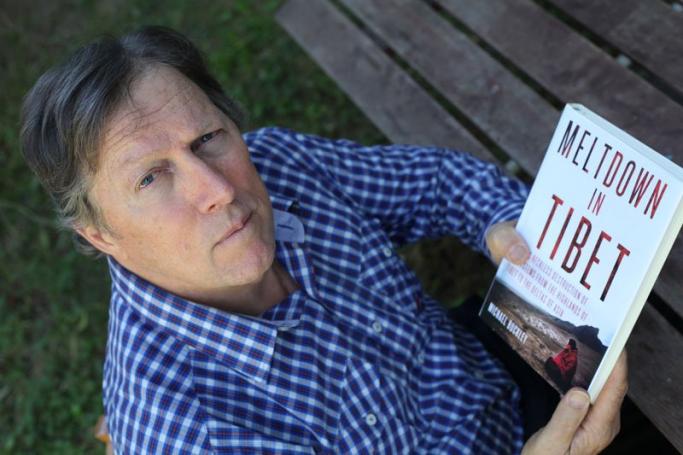

In late 2005, travel writer Michael Buckley visited Tibet to update a travel guide and learned about plans by the Chinese to dam the region’s rivers. On his return to Vancouver, he could find nothing in the Western media about the plans to dam the rivers, which include the Mekong, the Thanlwin (Salween) and the Brahmaputra. To publicise China’s dam building plans, Mr Buckley made a 40-minute documentary called Meltdown in Tibet, released in 2009, and followed it up with a book of the same name. Subtitled China’s reckless destruction of ecosystems from the highlands of Tibet to the deltas of Asia, the book was published last November. Mr Buckley gave a presentation on his book during the Irrawaddy Literary Festival late last month in Mandalay, where he was interviewed by Mizzima Weekly’s Mark Yang.

What are the biggest environmental challenges in Tibet?

The biggest is the melting glaciers. But that’s actually man-made because the melting is much faster than other parts of the world. It’s because of the increased CO2 in the atmosphere, but also black salt. And black salt is coming from biomass burning and from cooking fires, home fires. There’s a population of 1.37 billion in China and 1.27 billion in India; that’s a lot of people using those fossil fuels. Actually, black salt burn is solvable because if you use alternative forms of energy, there wouldn’t be black salt. Black salt is the tiny little black particles that land on the glaciers. Black salts absorb heat. That would be the biggest overall problem. But, in terms of other manmade disasters, I would say the dams are the really biggest problem.

Do the rivers that rise in Tibet have high potential for big dams?

The rivers in Tibet have the highest potential in the world to build big dams. They have the greatest elevation drops; that’s what dams need. Tibetan rivers have the biggest elevation drop in the world. That’s why they are so much interested in dams in the Himalayas. It’s not just China, it’s also India. And you have Bhutan building dams and Nepal buildings dams because of the altitude, the elevation drop. So all these countries in the Himalayas have very high hydro potential. But Tibet has the greatest of all. So in terms of potential, yes, there is a lot of potential to build the big dams. And also a lot of potential to destroy the rivers.

Who is building the dams?

It’s the Chinese state-owned companies, such as the Three Gorges Corporation and Sinohydro. There’s half a dozen of them. They are financed by state money. There are not private companies. It’s a state-run consortium. If you want to point a figure at anybody, point a finger at the Chinese leadership.

Li Peng, one of the former premiers, he is the one who got the Three Gorges Dam, which is 22 gigawatts, to get started. The Huaneng Group is run by his son, Li Xiaopeng, and his daughter runs another power company. Huaneng Group has been running projects on the Mekong. Any project to dam the Mekong has to go through Huaneng. It’s like they virtually bought the river.

How do dams damage the environment?

The biggest issue is the amount of water coming through. Flooding is part of a river’s natural cycle, especially the Mekong. It has annual flooding. China claims that damming the Mekong could control the flooding. But this is not what you need. You need natural flooding to support fisheries. This is on the Mekong. Cambodia relies on the annual flooding. If you don’t get the flooding, you are whacking up the ecosystem.

The next issue is fisheries. If you have a dam, you wipe out the fish migration. And to some extent, that is mitigated by aquaculture because aquaculture has taken off quite significantly in these countries as they couldn’t get a lot of fish anymore. If you put a dam on a river, it’s going to block a lot of fish transits. So, a lot of people turn to aquaculture. But aquaculture has its own environmental problems.

The biggest problem, the third issue, is silt, which is the nutrients that are carried by the river. Take the Brahmaputra, for example, an enormous amount of silt comes down every year. It supports agriculture, it supports the mangroves. Silt is sediment with a lot of nutrients in it. It’s like a cocktail of all the elements for growing things.

The silt comes down to the deltas where the rivers meet the ocean. If the silt doesn’t come down, the delta won’t be built up and it will start to sink. So it’s not just agriculture being affected but also the delta itself.

We have got half a dozen very important deltas, very big deltas. You have one in Burma: the Ayeyarwaddy delta. If you don’t have the silt coming to build up the delta, it will start sinking and salt water will come in and it’s going to ruin your crops because you don’t have salt-resistant rice yet.

The dam makers don’t want silt. They’ll be happy to let it through because it blocks the turbines. But, they have never figured out a way to do that, the same as they can’t find a way to let the fish through. So when you put a dam on a river, it’s like a huge blockage. Small dams are not a problem. Big dams are a problem because they damage the rivers. If you start altering the rivers, you get serious consequences.

What are the consequences?

Fertility downstream decreases which means the farmers have to use artificial fertilisers. Production costs rise because you have to buy the fertilisers. Beyond that, there’s great potential for disasters when you tinker with these natural systems. For example in Bangladesh and Myanmar, there’s a lot of mangroves. Mangroves are the front line of defence against rising sea levels and the best natural defence against cyclones.

Why is the himalayas region unsuitable for dams?

One reason is the risk of earthquakes. The Himalayas is an unstable seismic zone. So there are a couple of possible consequences. One is that building a dam in the region could trigger an earthquake and the other is that if an earthquake destroys a dam it is going to cause an inland tsunami that is going to wipe out entire towns downstream. After the Sichuan earthquake in 2008, the Chinese rushed to empty quite a number of dams because they were afraid of cracks in the dam walls. But they forgot to tell the people downstream, where there was massive flooding. But it was unexpected, so there were casualties.

Is Myanmar affected by China’s plans to build dams on rivers that rise in Tibet?

Sure, you got rivers like the Salween [Thanlwin]. The Chinese have started to build five dams on the upper Salween and they will be big dams, mega dams. They will take three to five years to finish them. But, once they are in place, it will have the same effects like what’s happening on the Mekong. They will disrupt the fish migrations, the flow of silt and the water supply can be erratic. The fisher-men who live on the Salween what will they do? Will they turn to aquaculture or fish farming? And then you’ve got the delta where the Salween enters the sea. The delta won’t be in good shape when the dams have been built.

The other river that the Chinese want to dam is the Ayeryawaddy, which doesn’t actually rise in Tibet but some of its tributaries do. The Chinese plan to build seven big dams on that river, including the Myitsone dam. It will all be done by one company, China Power Investment Corporation.

Any big dam will disrupt your ecosystem, and any kind of dam will be bad news for the delta. The Ayeyarwaddy delta will not be in good shape after the seven dams have been built.

Have you been to the Myitsone dam project site?

Yes, I have been there in a boat. I’ve seen the Chinese workers are still there. They are not going back home. The Thein Sein government says the dam will be postponed during the president’s term in office, which ends this year. I have two questions about the Myitsone dam. Why are the Chinese workers still there? Why are the people who lived there not allowed to come back?

Do you have a message for the Myanmar government and the Chinese companies that build dams in Myanmar?

You have got to put the environment ahead of everything. You have to do environmental impact statements before you build any dams. You have to figure out what are the impacts on the environment. Mother Nature does not recover sometimes. And you can’t put profit ahead of the environment.

Should the projects to dam the Thanlwin and the Ayeyareaddy be halted?

Yes, of course, because they don’t benefit the Burmese people. In several cases, the energy would be exported to China: 90 percent of the energy from the Myitsone dam was to be sent to China. Why destroy a river and a valley if your country is not getting any benefit. Myanmar has some serious energy problems but the electricity from the dams is not going to Myanmar.

Myanmar should weigh the consequences of bringing in mega projects which means mega dams and mega mining projects. I mean this is chaos. If you have a very big mine then you will start to pollute the rivers and you going to have serious consequences. If you can’t control it, it is better not to do it.

An upper Mekong dam underway. Photo: Michael Buckley

Development can result in damage to the environment. How can the Myanmar government find the right balance?

It’s better not to be greedy. It’s like the story of the golden goose. The goose lays golden eggs and eventually the farmer becomes too greedy and kills the goose to get the eggs. And there’s no eggs anymore. When people get too greedy, it creates problems.

Is there any evidence that the government is too greedy?

If you look at what they’re doing to the rivers, yes. I mean there’s no reason to build a cascade of seven large dams on the Ayeyarwaddy River. Why do you need seven large dams for a population of 60 million. You don’t need seven large dams, you need only one or two. Even then, they would damage the river. You have to weigh up what’s more important: the river or having the power you could sell somewhere else.

This Article first appeared in the April 23, 2015 edition of Mizzima Weekly.

Mizzima Weekly is available in print in Yangon through Innwa Bookstore and through online subscription at www.mzineplus.com