A good map of Asia will tell you all you need to know about life-giving rivers. The massive Tibetan plateau – or Third Pole as it has been called – is the source of water that literally nourishes millions if not over a billion of people in an arc from Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar and on into Southeast Asia, and China.

The mighty rivers that originate on the plateau – including the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Salween and Mekong – help supply water that supports people, agriculture, fishing, industry, and biodiversity on a massive scale.

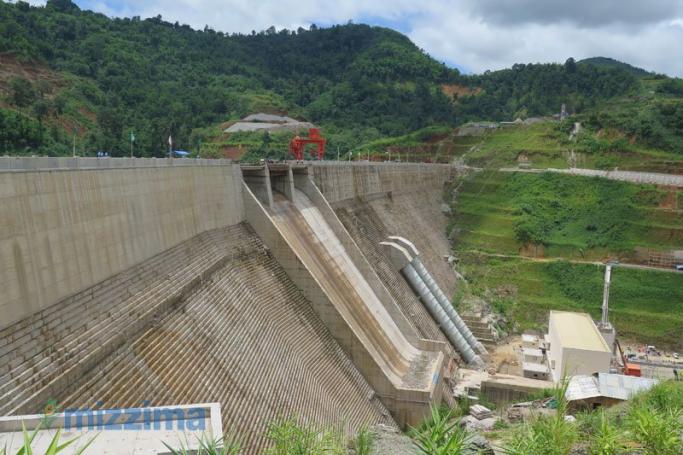

Yet for the governments and big business in the region, these rivers cannot be left alone. Across the region, plans are afoot to dam the rivers, to harness them primarily for energy through hydropower, as well as siphon off water for agriculture, industrial and household use.

Hidden crisis

The strangling of this Himalayan lifeblood is a largely hidden crisis. It is hard to collectively assess what effect dozens of dams on Asia’s major rivers are having and will have on life downstream.

Take the River Salween, or Thanlwin, one of Asia’s last free-flowing rivers, a river staring at an uncertain future. If the Chinese and Myanmar governments go ahead with plans for construction of a string of dams straddling this river and its tributaries, the Salween’s hydrology and aquatic life will be in danger. Millions will be displaced and the lives and livelihoods of some six million people living in its watershed will be hit. Environmental activists are drawing attention to the impact of hydro-power projects on the Mekong and its tributaries to make a case for halting the damming of the Salween.

Like the Salween, the Mekong originates in the icy peaks of the Tibetan plateau. After plunging down the mountains of the Yunnan province it leaves China to flow through or along the borders of Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam before emptying its waters into the South China Sea. The 4,345-km-long Mekong is Southeast Asia’s longest river. Its bio-diversity is second only to that of the Amazon. It is the world’s most productive inland fishery; Cambodians and Laotians catch the most fish per capita in the world. It is a veritable lifeline for Southeast Asians as it provides water, food and livelihood to millions.

China’s dams

China has built seven big dams across the Upper Mekong. While the full implications of mega dams for the environment and ecology will become evident only over the decades, some of the impact is already beginning to be felt in the lower reaches of this river.

For one, the dams are trapping much of the river’s sediment, resulting in reduced sedimentation downstream. Besides enhancing riverbank erosion this reduces the nutrients carried by the water and its capacity to nourish the delta. This, in turn, decreases soil fertility, impacting agriculture, rice production and food security.

People in the Lower Mekong Basin are complaining of sudden and sharp fluctuations in water levels. Sudden surges are destroying riverside vegetable gardens and devastating villages, they point out. Dams block fish from migrating upstream to spawn and returning fish that migrate downstream get trapped in turbines resulting in mortalities. It is causing a decline in fish numbers. This is undermining food and livelihood security. Besides several fish species have all but disappeared and the Mekong’s Giant Catfish has become a rarity.

More dams planned

Such problems are expected to deepen as more dams are erected and more rivers and tributaries are dammed in the coming years. China plans another 21 dams across the Upper Mekong, and the lower riparian countries are on a massive dam building spree as well. In the Lower Mekong Basin, eleven large hydro-power projects are in various stages of planning and implementation. Of these, nine are coming up on the main stem of the Mekong in Laos. In addition, Laos will build another 60 smaller dams on its tributaries. “A disaster of epic proportions” is unfolding in the Lower Mekong, says Kraisak Choonhavan, a Thai activist and former senator.

Is this the fate that awaits the presently untamed Salween as well? China proposes to build 13 dams across the upper Salween and Myanmar plans on seven on its lower reaches. Myanmar activists are drawing attention to reduced flow of water into Myanmar, a fall in fish catch and weakening of food and livelihood security of the Myanmar people. Millions of people could be displaced. The cascade of dams will have “major environmental costs” too, observes International Rivers Network. While the Hatgyi Dam is expected to inundate two wildlife sanctuaries in Kayin State, the Tasang Dam will flood teak forests and the Weigyi Dam will submerge parts of the Kayah-Karen Montaine Rainforests, the Salween National Park, and the Salween Wildlife Sanctuary.

Diverting water

China’s plans to harness the potential of rivers originating in the Tibetan plateau, especially the trans-border rivers has evoked anxiety in the lower riparian countries. Besides building hydropower projects on these rivers, there are projects too that envisage diversion of their waters.

Beijing maintains that its dams on trans-boundary rivers are runof-the river (RoR) projects that involve no storage or water diversion. It claims that “there will be no change in the quantum of the water flowing [in the River Brahmaputra] from Tibet” into India, Parag Jyoti Saikia, who researches hydropower construction in Northeast India at the Centre for Studies on Social Sciences in Kolkata, told this writer.

However, as Ramaswamy Iyer, a former secretary of water resources with the Government of India and currently an honorary research professor at the New Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research points out, even RoR projects can involve significant diversion of water. A “break in the river between the point of diversion to the turbines and the point of return of the waters to the river … can be very long, upwards of 10 km in many cases, even 100 km in some cases; and there would be a series of such breaks in the river in the event of a cascade of projects,” he writes in the Economic and Political Weekly.

As on the Mekong, so too on the Brahmaputra, known by Tibetans as the Yarlong Tsangpo, China is building hydro-power projects. And the lower riparian country, India has ambitious plans for dam building too. Around 150 mega dams and micro-hydel projects are being planned on the Brahmaputra and its tributaries. These dams “will significantly change the amount of water flowing in the Brahmaputra,” Saikia points out. Since the areas that will be affected by dam construction are forested, it will have “disastrous impacts for the rich bio-diversity, environment, ecology and livelihood of the people living here,” he says.

Over the past decade, South and Southeast Asian analysts have been debating the impact of China’s diversion of rivers. It South-North Water Diversion Project involves three routes to divert water from China’s water-surplus south to the arid and densely populated north. Of the three routes, the Western route is the most controversial as it involves rivers that originate in the Tibetan plateau, some of which are trans-boundary rivers. It envisages diverting water from the Upper Mekong to the Yangtze River and that of the Brahmaputra at the Great Bend i.e. just before it enters India. This, of course, will have ramifications for quantum of water flow to the lower riparian countries.

Enormous challenges

However, many feel that too much is being made about the water diversion project. Experts have drawn attention to the enormous technological and financial challenges involved in executing the project; diverting rivers in the western route, for instance, will involve hauling water up over high altitudes and treacherous terrain. Chinese scholars point that “given the potential negative impact” that such diversion will have on “relations with its lower riparian neighbours, particularly India, it is even more unlikely that the Chinese government will seriously consider the Grand Western Water Diversion Plan.” Indeed, as Grace Mang of International Rivers Network told this writer, “China’s diversion of Tibetan rivers has long been a minority view and is neither realistic nor seriously being contemplated by the Chinese government.” Thus while the implications of the Water Diversion Plan would be more far-reaching, it is the dams that are the clear and present danger.

The need for clean energy and economic growth ambitions is spurring governments to build dams. Dams on the Lower Mekong are expected to produce nearly 14,700 megawatts of electricity, enhancing Southeast Asia’s power generating capacity by 25 percent. It is its ambitions of emerging Southeast Asia’s “battery” that lies behind Laos’ energetic construction of hydropower projects. However, this power boost is coming at an enormous cost.

Myanmar’s actions

As Myanmar takes its next steps on the damming of the Salween, it would do well to study the experiences of its neighbours. India’s damming and storage of the Ganga’s waters reduced its quantum of flow into Bangladesh. The resulting high salinity of the soil in the Gangetic delta destroyed livelihoods, forcing millions to migrate. Many of them migrated to India’s Northeast, a region which is a cauldron of conflicts, insurgencies and ethnic wars. Their arrival in the Northeast impacted the demography of the region and added pressure on scarce resourcesand jobs. It impacted local identities and triggered new and more intense conflicts in the Northeast. These conflicts are expected to exacerbate with the damming of the Brahmaputra unleashing a new wave of problems.

Like the Brahmaputra, the Salween runs through areas where ethnic conflicts have raged for decades. Such conflicts will explode as the dams’ impact on the environment and livelihoods intensify.

In its journey through the Tibetan plateau, the Salween runs along an earthquake fault. Dams on this river are a recipe for disaster. In the event of an earthquake in the Tibetan plateau, dams could collapse. The resulting water surge in the Lower Salween will have catastrophic impact on Myanmar.

Dams on trans-boundary rivers in South and Southeast Asia have emerged a serious source of inter-state tension and conflict in these regions. Governments have decided unilaterally to dam rivers without consulting riparian states on their plans. A lack of transparency is driving uncertainty and tensions.

Dr Sudha Ramachandran is an independent journalist/researcher based in India. She writes on South Asian political and security issues and can be reached at [email protected]

This Article first appeared in the June 4, 2015 edition of Mizzima Weekly.

Mizzima Weekly is available in print in Yangon through Innwa Bookstore and through online subscription at www.mzineplus.com

You are viewing the old site.

Please update your bookmark to https://eng.mizzima.com.

Mizzima Weekly Magazine Issue...

14 December 2023

New UK Burma sanctions welcome...

13 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

13 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

12 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

11 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

08 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

07 December 2023

Diaspora journalists increasin...

07 December 2023

Conflict leads to cancelled constituencies in Chin State