As the Myanmar government mulls how to develop the country, the classic case of how South Korea transformed from an agricultural country to an industrialized powerhouse may not be the answer.

This was the assessment of leading Indian economist Prof. Jayati Ghosh, one of two leading Indian scholars invited to Myanmar to speak to government officials and the public about economic development paths for developing countries.

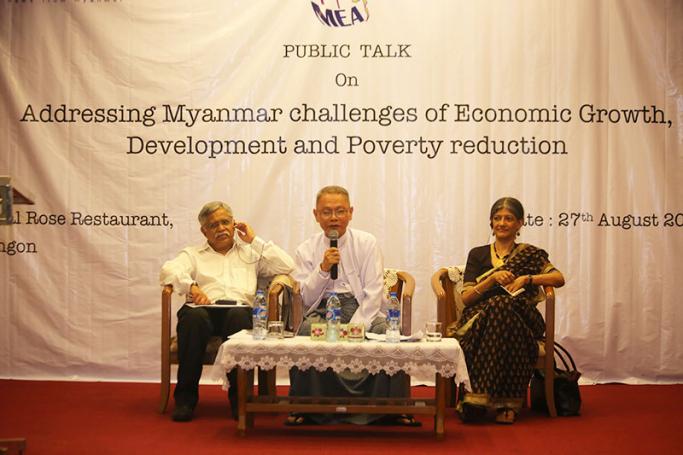

Prof. Jayati Ghosh was speaking at a public talk alongside Prof. C P Chandrasekhar on the subject: “Addressing Myanmar Challenges of Economic Growth, Development and Poverty Reduction.”

The talk was organized by Myanmar Economics Association, Mizzima Media, Renaissance Institute and ActionAid on August 27 at the Royal Rose Restaurant in Yangon. The event was attended by over 100 scholars and CSOs. The public talk provided a platform for a discussion on a range of issues and challenges of economic and social development of Myanmar.

In his introduction, Prof Kyaw Min Htun, President of the Myanmar Economics Association, said the purpose of the discussion was to debate ideas about the social economic development of Myanmar, especially now that it has an elected civilian government in place.

While both scholars said they were not intending to tell the Myanmar government what to do, their insights into how a range of countries had developed offered an insight into the pros and cons of the development models and approaches.

During the discussion, several Myanmar participants raised concerns about the Myanmar government’s approach to their economic policy.

“If you cannot have an export economy then you have to build up the domestic market so you can have a per-capita increase,” said one male participant. “You also need the distribution of the benefits of the production in a way in which the lower income groups at the bottom of the population see an increase in income. There must be a redistribution of income which is why you should have things like land reforms, security of tenure, work programmes, and so on so you can try to push up incomes so you have a mass market that can sustain a growth process.”

As one female economist told the audience, she was not clear on what economic policies the government is following after reading their public statement.“I think this is a very good vision document because it sets out things nobody can disagree with. Everybody wants those things. I think these are strategies in the process of becoming so it very exciting and fascinating for us to see. But this a point where it could go in any direction and the danger might be that so much of the advice comes from a particular mainstream kind of perspective that just by default you end up doing it. You repeat what everybody else is doing and often because it is presented as if everybody else is doing it, but they don’t tell you the real truth which is actually a lot of successful countries aren’t actually doing that.”

She noted that there is a tendency to say you should do everything you read, you should go in for that idea, you should deepen your financial markets by doing financial liberalisation, and you should have a bond market. With all of that kind of thing there is a danger with all of that. But we also heard there are people who are conscious about that recognising the need for caution. It would be nice if people in Myanmar got to hear more and more so people could decide what is best.

One participant wanted to know how the Indian government laid down its policy.

“I think as far as India is concerned it partly believes in looking east because of China,” said Prof. C P Chandrasekhar in reply. “It is because of the fear of China and their political problems they decided that if they don’t look east, they fear, and it may not be true, there may be somebody else coming in from the east. I think it is politically driven rather than at the moment economically driven. But now there is a feeling that India should get into other markets and so on. Basically I think it was an anti-China syndrome.”

Standard economic model

In her presentation, Prof. Jayati Ghosh pointed to the classic example of how over half a century South Korea developed from an agricultural country into an industrialized one, but warned that it was virtually impossible for a country like Myanmar to follow this path in this day and age.

“Out of all of the 180 developing countries, South Korea is the only country that has managed to do it. China is on track to do it, but it nowhere near this. Malaysia started to do it and then has stagnated. A lot of countries like Mexico, India, and Argentina have stalled, in fact some of them have de-industrialized,” she said.

The South Korea model might be the ideal but it is not inevitable, it is unusual, and it is not easy. “So if we want to get there we need to look at how we can achieve this and recognize that very few countries have managed to achieve it. So it requires clear strategies.”

How to classify development

As Prof. Jayati Ghosh outlined, there are many ways to classify “development.”

As she said, the tendency was for countries such as India, China or Brazil or maybe even Myanmar to look at GDP per capita as the indicator. “But of course we know there are many, many other ways, there are multidimensional ways of looking at it,” she said.

“I am going to take ‘development’ here to mean something very specific. Basically, I am going to say it is productive diversification - that is the shift in the economy from low value-added to high value-added activities in terms of production and in terms of employment.

She said that here the development is productive transformation. This can happen through a movement across sectors, from agriculture to industries to services, or it can happen within sectors, with agriculture becoming progressively more productive, all of these sectors becoming more productive in themselves.

As she said, people tend to think of the classic model of how South Korea developed in the wake of the Korea War in the mid-20th Century.

As she pointed out, as per capita income went up in South Korea, agriculture went down from more than 65 percent to less than 10 percent.

“The real story was that agriculture needs less and less people, a rising GDP but a falling share in people employed,” she said.

“So what they found was the share of industry in output keeps rising, noting it rises from a low percentage of less than 10 percent to about 30 percent. So this is an industrializing economy, so that by the end of the period charted it is an industrialized economy.”

As she noted, the share of workers rises in industry but from the mid-1990s the percentage of people employed begins to fall because industry becomes more and more productive, and you need less and less workers to produce that rising share of output. So that difference is going into the services employment, but it is going into services employment at a higher level of income. That is very important. The shift towards services employment occurs when the per capita GDP is already quite high. And that is what enables the people in services to also get higher wages.

“This is the classic pattern that all of us want to do,” she said.

Consider different strategies

Prof. Jayati Ghosh said such an approach is virtually impossible to replicate today.

She said there was scope for a country like Myanmar to consider using different strategies. This was important as people are often told there is one kind of strategy you should follow which is neo-liberalized markets, FDI and so on.

“It is important to remember that South Korea did not use those strategies. South Korea did not have open markets until very, very recently. South Korea did not rely on FDI [foreign direct investment]. South Korea did not open up the financial sector until very recently. So there isn’t only one trajectory. It is not true that there is no alternative to a certain set of policies. In fact, to be smart in today’s world you really have to have a different kind of toolbox where you are not only using the mainstream established prediction because that is the one that doesn’t really work for most countries.

The need for planning

“So what is required? First, it requires planning. I realize that planning can be a bad word, especially in a country which has experienced in a way the worst kind of central planning.

“In terms of planning, one should be thinking five or ten years ahead, not just this year. What is needed is a coordinated strategy for the medium term. It requires trade and industrial policies. It requires financial policies, especially directed credit. In fact all the successful countries in history, beginning with England and Germany, Japan and South Korea, all the successful countries used directed credit. And it required social policy. This is not something people think of as a natural part of the development strategy. But I want to argue that it is an essential part. That in fact you really cannot achieve successful development without social policy.

“Now all of this means you need more government and again I realize that more government is a bad word. In this specific historical context you have experienced. You have experienced the worst kind of unaccountable government.

“On the other hand, we know that these are not things that markets deliver necessarily on their own, you necessarily have to have a role for the public sector and public intervention. The critical thing is to make sure this public intervention is transparent, it is accountable, democratically-decided and it is responding to social needs.

Not just for a small elite

Prof. JayatiGhosh hinted that a change was needed in how Myanmar runs its economy.

“So that is the challenge of this democracy to make sure that you a balanced active intervention but that it is transparent and socially accountable, because you cannot achieve the development without the role of the State. But it is very important to make sure that State is operating in the people’s interests and not in the interests of a small elite.”

On the issue of trade and industrial strategies, Prof. Jayati Ghosh said Korea, Japan or Singapore all used extensive industrial policies in all kinds of ways. “Many of those are not available to us. It is a different world. It is the 21st Century, we have WTO, we have trade agreements, and we have ASEAN trade agreements. You can’t do many of the things that they did. Sadly.”

Local content

She stressed the importance of local content. And how it was important to move from exporting raw products to making sure these products were processed before export, citing the case of the Congo in Africa, where the country had moved from the export of raw copper to processed copper.

As she pointed out, in the last few years, the global raw copper price has dropped and the market has collapsed but processed copper prices have not collapsed as much, and the market has not collapsed as much. So the processing of a raw material such as copper has a potentially positive role.

She pointed to the controls in the Dominican Republic on timber exports and how this same process could help in Myanmar to develop a domestic furniture industry, something Malaysia also did.

And she questioned the focus on big companies and multinationals.

“Often we think about industrial polices only about very big guys, multinationals, big domestic companies. In fact, it should not be. You can focus your industrial policy on micro, small and medium enterprises, including agriculture, which basically means they get access to credit, infrastructure, input, and marketing. It is a very different vision to only giving subsidies to very big producers. You are making sure agricultural producers have access to all-weather roads, to knowledge about latest kinds of seed available, knowledge about how to use organic technologies, and how to access organic marketing.

Leveraging LDC

Myanmar’s status as a Least Developed Country (LDC) could be beneficial as it seeks to develop and engage with international and regional bodies, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

“In Myanmar you have a lot of advantage because a lot of your agriculture is organic, simply because you didn’t get to the chemical use. You can use public policy to help in organic certification, because there is a growing niche market for organic products. And it is a massive increase in value. If you get certified as organic, you get three times the price for just a normal export of that commodity.

“Now you will say, how can we do this because we are in the WTO, because local requirements are banned. In fact they are not banned. Local requirement within the WTO rules are only for foreign producers. You should be in a position to apply it for everyone.”

As Prof. Jayati Ghosh said, Myanmar can exploit the fact that it is a Least Developed Countryand can exploit that within the WTO. “You can benefit because the WTO does not enforce with the same rigidity.”

“Similarly in ASEAN, you are not ASEAN Six, you are ASEAN Plus and that makes a difference.

Care with treaties

The Indian economist noted that care needed to be taken with treaties.

“One thing that is important is the kind of treaties you get into and I am sure now the government will be entering into more and more international treaties, bilateral treaties and other free trade agreements,” she added.

She warned about the kinds of restrictions these treaties can impose. “And be careful in the negotiation. And again you do not need to take what is on offer.”

As she noted, companies have taken governments to court and the companies have won in virtually all cases.

As she said, more and more countries have gone back on earlier investment treaties. Eight countries in Latin America, five countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, rejected their earlier bilateral treaties, renegotiated them to actually make them less investor friendly and more domestic human rights friendly.

South Korean development model ‘not the answer’ for Myanmar: Indian economist

28 August 2016

South Korean development model ‘not the answer’ for Myanmar: Indian economist